UNA-UK speaks to Diane Corner, a former British diplomat who served as Deputy Special Representative and Deputy Head of the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA) from July 2014 to June 2017.

What do you see as the purpose and value of UN Peacekeeping?

The United Nations, representing the international community as a whole, has the unique capacity to forge an international consensus, mobilise the necessary resources, and respond to a problem with an authority that no other organisation can match. Of course, it’s not always possible to reach an international consensus, and even when it is, UN engagement doesn’t necessarily proceed smoothly – in fact it almost invariably faces huge challenges. UN peacekeeping is trying to solve some of the most difficult and intractable conflicts in the world, and there are no easy solutions.

UN Security Council Resolution 1325 tasks the UN with looking at peace and security through the lens of gender. How effectively have you seen this put into practice?

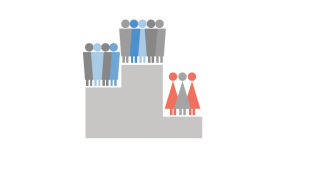

There have been great strides forward in some aspects but in other areas there remains more to do. Secretary-General António Guterres has been quick to address the issue of women’s representation in peace operations, setting ambitious targets for early progress. There is also already much good work within UN missions to respond to women’s specific experience of conflict. Yet more needs to be done to involve women fully in all aspects of bringing a conflict to an end. This is something the international community as a whole should champion. You cannot build peace if you exclude half of the population and, empirically, that half which is least conflict-prone.

Is UN peacekeeping still a masculine world? How does this shape the UN’s response?

In terms of percentages of women in missions, UN peacekeeping remains a very masculine world because the largest components of peacekeeping missions are military, and they are still overwhelmingly male. That will only change if troop-contributing countries change their military recruitment and promotion policies, and also put a premium on the skills needed for UN peacekeeping. For example, while peacekeepers may need to take robust action, they also need to build trust with the local population, and that can be much easier if you have women involved.

The 2015 High-Level Independent Panel on Peace Operations (HIPPO) called for more people centred peace operations. How can this be translated into a new approach to peacekeeping, and what role will local women and women’s groups play in the transition?

These days a UN peace operation is more likely than not to be deployed into an arena where there is no peace, where the structures of the state may be very weak, and where the UN has to underpin international efforts to bring the conflict to an end. This is the situation [the UN peacekeeping operation] MINUSCA faces in the Central African Republic. Of course, this work involves engaging with leaders at national level but it also includes local-level work to analyse what is happening, put in place and monitor local ceasefires and tackle outbreaks of violence to build peace from the ground upwards. It’s a very different approach from the early days of UN peacekeeping, and the change reflects the immensely complex theatres in which the UN is now operating.

As one of the most senior British citizens in UN peacekeeping, how do you see the UK’s relationship with peacekeeping? Could we do more?

The UK’s contribution to UN peacekeeping, which includes personnel, resources and expertise, is highly regarded. The UK is the biggest donor to the Peacebuilding Support Fund, in many conflict situations the UK is one of the biggest donors to UN agencies, and the UK is recognised as having particular expertise in post-conflict stabilisation. Indeed, there are great similarities with the UN’s approach on stabilisation issues, for example on security sector reform or disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration.

I would, however, particularly want to emphasise the importance of the military contribution that the UK can make – and indeed is making – to a number of missions. British armed forces have unparalleled expertise, built up over seven decades, in modern counter-insurgency. Very few militaries come to the UN with anything like that kind of experience, and given the conflicts into which UN missions are now deployed, that skillset is of critical importance. For example, in the mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, a small number [five] of UK staff officers made a big impact on the mission’s effectiveness. How much the UK can contribute inevitably has to be weighed against other priorities, but I would stress that the UK should not underestimate the value that it can bring to UN peacekeeping.

You were Deputy Head of MINUSCA, the UN mission in the Central African Republic (CAR), which has faced incredible challenges but also deserves credit for stopping potential atrocities. Could you give us an overview of MINUSCA and what the future may hold for the mission and for CAR?

MINUSCA is indeed an incredibly challenging mission. Since the mid-1990s there have been around a dozen international engagements in CAR, and at least as many peace deals, and none has had a lasting impact. There are many contributing factors to the conflict: a very weak state and almost non-existent infrastructure; a plethora of armed groups, most of whom have no agenda other than personal enrichment; bad governance; predatory elites; and all this in a vast territory – CAR is the size of France and Belgium combined. It’s also a source of conflict minerals in a region scarred by war. In addition, regional movements of nomadic cattle herders into CAR’s lush pastureland each year also provoke tensions.

Since 2014 MINUSCA has focused on the west and the centre, where most of the population lives and which saw the greatest violence in 2013–15, and these regions are now much calmer though still fragile. Since mid-2016 there has been an upsurge in violence in the east, linked in part to the withdrawal of the African Union (AU) Regional Task Force, which was fighting the Lord’s Resistance Army.

Despite the difficulties, MINUSCA protects tens of thousands of civilians every day, and without the UN’s presence in CAR there would have been a genocide. Personally, I think that success in CAR hinges on whether those guilty of terrible crimes will be punished. It is critically important to support the work of the International Criminal Court and the CAR Special Criminal Court – their work is key to bringing the violence to an end.

How do women living in CAR view MINUSCA? How does that compare to your experiences in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Sierra Leone?

MINUSCA’s work to support women’s rights, including to the passage through parliament of the Gender Equality Act, has been very much appreciated by women’s groups in CAR and so too has been the work with other UN agencies to combat conflict-related sexual violence. That said, I’m not sure if there are sharp distinctions between the perceptions of the broad mass of women and those of men. There is perhaps a greater distinction in the perceptions of those living in the capital Bangui and those outside, particularly in areas where security problems are rife and where MINUSCA is the only source of protection, as shown by large IDP camps close to the Mission’s bases. Within Bangui civilian perceptions of MINUSCA are more mixed, partly due to political factors – UN Missions are an unwelcome presence for those who seek to benefit from continued chaos.

MINUSCA grew out of an earlier African Union (AU) mission, which in turn grew out of various military interventions by France and neighbouring powers. How did cultures and attitudes within the mission shift among the mission personnel once they were ‘rehatted’ with the famous blue helmets? How can UN values, particularly on gender, be instilled?

The UN has a wealth of experience in and doctrine on peacekeeping, and it has also on several occasions re-hatted troops from another peacekeeping operation. But while a comprehensive programme of training and support was put in place for the re-hatted troops, including on gender issues and sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA), elements of that programme were disrupted by the ongoing conflict in CAR. Also, it’s now clear that the sheer scale of rehatting six out of a total of ten battalions (four of whom had never served in a UN mission before) and retraining them in theatre was over-ambitious and contributed to the problems SEA that MINUSCA experienced. The UN has learned a lot of important lessons from what happened in MINUSCA. The best way to prepare contingents for service in a UN mission – including on gender issues - is to train them properly before they deploy.

MINUSCA was once notorious for its levels of sexual exploitation and abuse, although many incidents took place before the mission was under UN auspices. How was the issue brought under control?

The mission still has too many cases – even one case is one too many – and within the UN we should never be complacent that SEA is a problem which has been brought under control. But it is true that the number of cases in MINUSCA has declined of late, due to a number of strands of work. First, the mission leadership recognised the critical importance of dealing with this problem. It led an intensive campaign within the mission on zero tolerance for SEA, backed up by concrete measures, including the removal of two battalions (750 troops each), and a company (120 troops), and suspected perpetrators or those who had neglected their duty to prevent SEA. Second, we resolved to be transparent about the problem, even when that put us at the receiving end of international opprobrium. Third, we sought to put the needs of victims at the heart of our response, working with the UN country team and humanitarians to provide support. Fourth, we strengthened capacity in the mission to lead on victim support, on the handling of cases and on the media aspects. It was a huge amount of work, but it was vitally important to get this right – for the mission and the wider UN system, and above all for the victims.

Why has the UN found SEA to be such a difficult issue to tackle?

I think that the UN, like so many organisations and institutions as we know now, failed for a long time to recognise the scale of the problem it had on its hands. Crimes of this nature are often hidden. Victims do not readily speak out, even more so in countries where they may be subject to reprisal for doing so, and where the institutions of justice do not exist. Of course that should have been recognised years ago.

If there is a silver lining to what happened in MINUSCA, it is that the UN’s approach to SEA has been transformed, with a senior team devoted to eradicating the problem and to supporting victims; with transparency on the number of cases; with much greater vigilance within missions; and with mission leaders held to account for their performance in tackling SEA. But the very low rates of conviction for those accused of committing SEA remains a cause for concern and troop-contributing countries still need to tackle this.

Without the right policies and structures in place, SEA can be found in every country and every organisation. That has to stop. I hope that the backlash we are now seeing in response to scandals in the entertainment industry, politics and elsewhere, marks a watershed in ensuring that women everywhere are treated with respect. And the UN’s rightful place is at the forefront of these efforts.

Diane Corner is a former British diplomat who joined the UK Foreign & Commonwealth Office in 1982. Her postings included Kuala Lumpur, Berlin, Harare, Freetown, Dar es Salaam, Kinshasa and Brazzaville, before her UN appointment. A selection of four questions from this full interview ran in the print version of the magazine.

Photo: Gladys Ngwepekeum Nkeh, a UN Police officer from Cameroon serving with MINUSCA, conducts a class on gender violence at a school in Bangui, Central African Republic, October 2017 © UN Photo/Eskinder Debebe