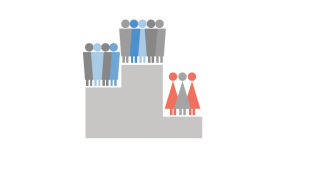

Whilst championing human rights abroad, Britain is failing at home. Discrimination and detention are a common reality for women seeking asylum in the UK. How can the government build a stronger global Britain, aligned with international law and the principles of the United Nations, if it falls short on protecting the most vulnerable women within its own borders?

The British Government has committed to respect and advance human rights, including by advocating for gender equality.

However, on their last visit to the UK in April 2014, the UN Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women (VAW) reported “The UK’s standards for dealing with violence against women and girls (VAWG) in relation to women seeking asylum compare poorly with those for women experiencing VAWG in the UK or abroad, demonstrating a lack of due diligence and joined up government.” Furthermore, Rashida Manjoo, UN Special Rapporteur between 2009 and 2015, concluded that "poor quality decision-making in women’s asylum claims leaves them vulnerable to VAW in the UK”.

Women asylum seekers are kept in Immigration Removal Centres (IRCs) whilst their asylum requests are processed. These detention centres are similar to prisons: they are not allowed to leave, they are watched and controlled by staff and they can rarely contact the outside world. According to several reports by Women for Refugee Women, women in these centres are vulnerable to abuse, persecution, humiliation and discrimination. The charity Medical Justice has presented evidence of torture, medical mistreatment and segregation in their report A Secret Punishment. Their extensive casework also reveals the lack of access to health care and the toxic effect of detention itself on the health of detainees.

The largest detention centre for women is Yarl’s Wood. Women detained there have said that it revived the traumatic experiences that led them to apply for asylum in the first place. Several organisations and unions have come forward to protest against the detention centre and demand that Yarl’s Wood is shut down. Some of these groups propose a more inclusive and open approach to asylum, where women can integrate into local communities.

From the perspective of someone who has been to one of the Yarl’s Woods demonstrations, I can only express the frustration and injustice felt when looking at the women behind bars. Women like Margaret, a mother of three children, originally from the Democratic Republic of Congo, who have been persecuted and tortured in their country due to political beliefs. Luckily, I get to freely express my own. In the last protest, looking at the women locked up by the walls of the UK’s Immigration and detention system, I realised that had I been born into persecution I could have been there.

In the process of seeking asylum in the UK, when women are interviewed (often having to retell traumatic incidents including violence, abuse and torture) they often have to speak to untrained staff, and with no childcare available. Mothers therefore face a hard choice: they either share their traumatic experiences in front of their children, or they refuse and risk failing their application. Women, already more vulnerable to abuse such as sexual and gender-based violence, female genital mutilation and forced marriage, are therefore frequently placed at further disadvantage in their quest for safety.

The imprisonment of women asylum seekers in detention centres contravenes the guidance of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, which states that: “Victims of torture and other serious physical, psychological or sexual violence also need special attention and should generally not be detained.”

Last year, the Home Office released the policy “Adults at Risk in Immigration Detention”, stating that adults at risk are vulnerable people that should not be detained. Previously only victims of non-sexual torture were given this right, victims of sexual violence were excluded. The policy now considers adults at risk “those who have experienced a traumatic event, such as trafficking, torture or sexual violence”.

Women for Refugee Women recently released a new report. “We are still here: The continued detention of women seeking asylum in Yarl’s Wood” which exposes how the “Adults at Risk” policy is failing to safeguard and protect vulnerable women. Instead, it is making them more vulnerable in detention. It has also failed to reduce the number of people in detention centres. When the policy ‘Adults at Risk’ came in, they were 2,994 people detained. One year later, the number is 2,878.

The Women’s Asylum Charter is a civil society initiative that sets outs the fundamental rights of female asylum seekers in the UK. It has more than 350 signatory organisations. It suggests that the UK commit to treat women seeking asylum in the UK with respect for international conventions and to support the promotion of a gender-sensitive culture. The UK Government has not made much progress on these issues, although in April 2016, Parliament approved a 72-hour time limit on detaining pregnant women.

It has been a priority for the UK Government to play a role in enforcing human rights laws, and in the promotion of global values, But Britain can only speak out on abuses outside its borders with credibility if the most vulnerable within Britain are protected and are at the heart of government policy.

In the Keeping Britain Global report, UNA-UK calls for a joined-up approach to the UK’s role in the world. At a time when the international community needs to come together to solve issues collectively and overcome global challenges, Britain needs to use its position to build a better world for everyone, including women asylum seekers and refugees. This means reforming its own institutions.

Photo: Demonstration photograph by Peter Marshall