- Jayati Ghosh - Tackling Poverty and Inequality

- Dan Plesch - Eradicating Weapons

- Pok Yin Stephenson Chow - Protecting Human Rights

- Ahmed Shaheed - Fighting Intolerance

- Sarra Tekola - Pursuing Climate Justice

- Victoria Tauli-Corpuz - Struggling for Inclusion

- Ramesh Thakur - Preventing Mass Atrocities

TACKLING POVERTY AND INEQUALITY

Development can mean many things, but one way of conceiving it is the movement to a world in which the accident of birth does not play such a huge role in determining life chances as it currently does.

Location continues to account for around half of international income inequality, and it is no accident that the poorest areas are in the less developed former colonies that became the happy hunting ground of both old and new imperial powers. In addition, domestic differences, such as class, gender, race,

caste, ethnicity and other social attributes, also matter hugely in denying people the opportunities or fruits of development.

International institutions are – at least on the face of it – all about development and inequality reduction. But the activities of bodies like the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank have long been seen across the world as part of the problem, perpetuating neo-colonial division of labour and preventing governments from privileging the human rights of citizens over the legal rights of companies. Their policy advice is presented in supposedly “technocratic” terms, failing to recognise that decisions affecting distribution (both national and international) are deeply political.

Other parts of the UN system therefore have an important part to play in correcting this imbalance. But sadly, over the past decades, they have been less successful in playing this role, and more likely to get caught up in passing development fads (ranging from microfinance to cash transfers) that are presented as silver bullets for development and poverty reduction. All too often, UN agencies end up supporting strategies being pushed by large global corporations, rather than providing an effective counterbalance to growing corporate power.

Yet the UN and its various agencies still form the most viable framework within which to fight for global justice and human rights. They must be revitalised and energised to fulfil this important task.

JAYATI GHOSH Professor of Economics at the Centre for Economic Studies and Planning, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University

ERADICATING WEAPONS

Issues of race and neo-colonialism pervade both UN and global efforts at disarmament. The tacit acceptance by major powers of a nuclear-armed apartheid South Africa, followed by a near panic that a nuclear bomb might come under Nelson Mandela’s control, illustrates the case in stark terms.

The same attitudes pervade efforts to reduce conventional weapons. The rhetoric of legitimate and illegitimate weapons counts the Anglo-Americans as legitimate acquirers of unlimited conventional arms, despite wars of aggression, such at that against Iraq. Arabian despots allied to the West are favoured while Iran and North Korea have been demonised, and Israel allowed a free pass.

Good news on disarmament from the developing – read, non-white – world is routinely buried and ignored in Western debates. The nuclear-free zones across Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, South-East and Central Asia and in the Pacific are discounted by self-styled realists buried in a pre-atomic delusion that nuclear arms can be kept forever without a nuclear war.

At the UN, it is non-aligned states that keep up the pressure on disarmament, by insisting to nuclear states that disarmament is not merely realistic but essential. UN Secretary-General Guterres’ initiative on world disarmament is an opportunity that all supporters of the UN should rally behind and carry forward. It is the first full set of proposals on disarmament ever brought forward by a Secretary-General – in large part the result of calls from outsidethe nuclear-armed alliances and powers of the global North.

The devastating impacts of conventional war in places such as Syria and Yemen should serve as an urgent call to action that humanity as a whole must grapple with disarmament. North-South dynamics continue to shape debates at the UN, but while important, they cannot and should not be used as an impediment to progress on this vital agenda.

DAN PLESCH Director of the Centre for International Studies and Diplomacy, SOAS University of London, convener of The Strategic Concept for the Removal of Arms and Proliferation (SCRAP), and author of the online course: Global Diplomacy: the United Nations in the World

PROTECTING HUMAN RIGHTS

Intersectionality has become an important part of women’s rights advocacy, as it promises a more nuanced understanding of the multifaceted experiences of women based on multiple identities such as race, gender and class. However, applying this concept to international human rights law has proved challenging.

When we speak of ‘identities’, we are often invoking socially constructed representations of difference. In international law, this has produced a focus on the exclusionary effects and consequences brought about by more than one of these representations whilst ignoring another understanding of identity – i.e. the ways in which we feel, understand and identify ourselves.

As a result, when mechanisms such as the UN human rights treaty bodies, which monitor compliance with instruments like the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, address practices such as veiling, they tend to assume that it is a practice imposed because of gender and cultural/religious membership as opposed to a practice that a woman willingly engages in or something that she feels morally compelled to do.

So how should we understand the practice of veiling? Women who veil are often caught at the intersection of prevailing discourses in which gender and religion play only a part. Exclusionary politics founded on nationalist sentiment and anti-Islamism also play a significant role in the battle over what is supposedly the real meaning of veiling. This has an effect on how actors regard themselves: even if not all women who veil agree with the practice on traditional or religious grounds, they may continue to do so to resist the political discourse which demeans them as members of that tradition/religion.

The lesson for our treaty bodies is, therefore, that in examining discursive practices it is important to acknowledge the very nature of such practices as the site where contradictory discourses compete for dominance. To avoid outright endorsing (and thus reinforcing) a particular discourse, intersectional analysis requires a thorough examination of the context in which these discourses are produced and reproduced, and how they affect the actual experience of individuals.

POK YIN STEPHENSON CHOW Assistant Professor at the School of Law, City University of Hong Kong

FIGHTING INTOLERANCE

Responding to rising intolerance based on religion or belief and race requires paying attention both to the overlaps and distinctions between these two forms of hatred.

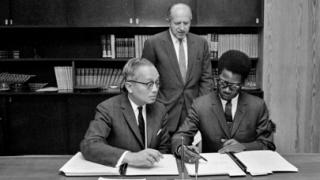

The UN began to examine racial and religious intolerance jointly in 1960, in response to outbursts of anti-Semitism. However, in 1962 the UN decided to develop separate normative protections for religion and race, with the latter pursuit producing the 1965 International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD). A treaty on freedom of religion or belief remains pending.

In practice, however, it has proved difficult to compartmentalise these two issues. The UN special procedures mandates on religion and race frequently work together, especially through joint communications to countries. The ICERD Committee’s jurisprudence shows that it does not regard religious intolerance as an independent basis for intervention. Nevertheless, the Committee seeks information from countries about the situation of ethno-religious communities.

Racism and religious intolerance frequently overlap. Race can be a fluid, floating marker, and a shared culture or shared religion can engender a racial identity regardless of descent or chosen identities. In the case of anti-Semitism and intolerance towards Sikhs, the overlap is evident. In other cases, as with Christians, Muslims and many others, religious markers can become core features of ethnic identity.

Despite the frequent crossover, it is important to observe the conceptual distinction between these two phenomena, while advancing human rights protections. Article 4 of ICERD, for example, prohibits the dissemination of ideas of racial superiority. Applying a similar restriction in regard to religion or belief, however, could destroy the essence of freedom of religion or belief and also undermine other human rights.

The way to ensure there is no gap in protections is not to ignore the important distinctions and overlaps between race and religion, but to take a holistic approach to human rights and to ensure that we pay attention to the lived realities of the intended victims of intolerance. We must also focus on the thresholds of risk and the triggers of violence and discrimination.

Accountability for violations and redress for victims are crucial, as is implementing a preventive approach that pursues positive measures to promote societal cohesion. These can be more effective than lowering the threshold at which criminal sanctions are imposed.

The Rabat Plan of Action and Human Rights Council Resolution 16/18 – which seek to tackle issues such as negative stereotyping and incitement to violence through measures including education, training and media codes of conduct – provide useful guidance in this regard.

AHMED SHAHEED UN Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief, Deputy Director of the Human Rights Centre at the University of Essex and a Maldivian diplomat who served twice as Minister of Foreign Affairs

PURSUING CLIMATE JUSTICE

Addressing climate change is going to take more than technological advances. We must start at the root, changing the power structures that uphold colonialism. It is often stated that countries in the global South are the least responsible for, yet most affected by, climate change. What is not discussed,

however, is why.

The industrialisation of the global North, through the exploitation of resources from the South, is the largest contributor to climate change. Through colonisation, the North stole resources, land and labour and subsequently developed in ways that now insulate its people from many climate impacts.

This unequal exchange of ecological capital continues today through free trade agreements and structural adjustment policies that are forced upon developing countries – an oppressive form of economic neo-colonialism. The UN Development Programme has long been critical of conditionality, particularly the intense pressure exerted by international financial institutions during the 1980s and 1990s to abandon national projects and nationallydriven priorities in favour of unprotected participation in the international market. However, a global system of supremacy continues to keep the South economically poor and more vulnerable to climate change.

True climate justice must include reparations from the colonisers to the colonised, and the UN’s Green Climate Fund offers a vehicle to provide this. Rich countries tend to see their contributions to the Fund as voluntary assistance – a charitable act – rather than what it should be: a mandated responsibility.

Without such a mandate, responsible parties will continue to deny their role in the destabilisation of entire regions. How can action on climate happen when we fail to acknowledge its inextricable ties to race, colonisation and privilege?

As with so many issues, climate change disproportionately affects people of colour, and issues that do so invariably remain unaddressed. If all lives truly mattered, we wouldn’t wait to tackle climate change until white people’s lives were being threatened. Currently, it seems that global climate negotiations are aimed only at protecting white people’s standards of living. A colonial racial hierarchy is still in effect via the actions and policies of all of our modern institutions – a hierarchy that is one of the biggest hindrances to global co-operative climate action.

SARRA TEKOLA Black Lives Matter activist and scientist who is currently studying for a PhD in sustainability at Arizona State University

STRUGGLING FOR INCLUSION

Indigenous people have always had to struggle to be heard at the United Nations. It is never a given that we will have a voice in international institutions, and indeed we have often had to protest on the margins before being granted our rightful seat at the table.

The groundbreaking 2007 UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples was the product of decades of advocacy from indigenous peoples from around the world. It took years until the UN finally started to draft the declaration in 1982, and formal discussions only began in 1995. At that time, we were told that we were not allowed to speak in the negotiations. We could only observe. But we refused to legitimise yet another decision made about us without our participation or consent, so we walked out, and won the right to participate formally.

The declaration that resulted is still at the heart of indigenous peoples’ global advocacy. It recognises our unique rights as peoples who have suffered generations of violence, discrimination, land grabbing and the denial of our right to our customary lands. Since its adoption, it has been the basis for numerous victories in the form of new laws recognising our land ownership, titles granted for indigenous territories, court decisions that uphold our rights and increased participation in international platforms.

Our standing at the UN has come a long way since we walked out of the declaration negotiations. Indigenous voices are heard far more often in New York, Geneva and other international platforms. Indigenous leaders from around the world now participate in every major climate conference. We are part of the Paris Agreement and the Sustainable Development Goals, and there is growing recognition of our contributions to sustainable development and climate change. I am proud to be the first indigenous woman to be appointed UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples.

Challenges remain, of course. It can be difficult to meet governments and international actors when the reality on the ground so often still involves violence, legal harassment and the failure to recognise our rights – but we have a lot of cause for hope. Much more than in the past, indigenous peoples have

a voice in discussions about their rights. I only hope the world will listen.

VICTORIA TAULI-CORPUZ UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples and an indigenous rights activist

PREVENTING MASS ATROCITIES

(An abridged version of this article ran in the print version)

Tyranny is not restricted to any particular religion, culture, civilisation or gender. Political rule based in terror rather than citizen’s welfare, safety and security is a universal moral failing. The Westphalian system of sovereign states spread from Europe to cover the whole world after decolonisation. Because it was seen to have sanctified the ability of tyrants to rule by terror - free from external restraints and counter-measures - the need arose for a matching universal norm to ban and stop atrocities.

One of the most important developments in world politics in recent decades has been the spread of the idea that there exists a responsibility to protect (R2P) people threatened by mass-atrocity crimes – vested in individual states at the national level and in the UN Security Council at the global level.

R2P was articulated by the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty (ICISS) in 2001 and unanimously endorsed by world leaders at the UN in 2005. For advocates, it is a poster child of liberal internationalism, summoning forth the better angels of human nature to save strangers in distant lands within a rules-based global order. For critics, it is the enabler of choice for powerful countries to appropriate the language of humanitarianism when violating the sovereignty of weak nations.

The notion that R2P is an updated version of the old “white man’s burden” can itself be racist. It denies agency to developing countries, insisting they can only be victims. It suggests their citizens should either be left to the mercies of thuggish leaders, or to the ad hoc geopolitical calculations of powerful Western countries, rather than to globally validated norms and due process.

It ignores the origins of R2P, agreed in the aftermath of the 1994 Rwanda genocide, 1995 Srebrenica massacre and 1999 Kosovo intervention, and driven by African and European victims. It also ignores the indigenous traditions in many parts of Asia and Africa that hold rulers owe duties for the safety, welfare and protection of their subjects. For instance, the Hindu concept of rajdharma means duty of rulers – a point that was made by then-Prime Minister A.B. Vajpayee to the then-state Chief Minister Narendra Modi, of the same political party, in relation to his failure to protect 2,000 Muslims killed in targeted violence in Gujarat in 2002.

The Genocide Convention converted the moral revulsion of the Holocaust – a failure of Western civilisation – into a binding universal norm. The two humanitarian crises that most drove the push for R2P were the Rwanda genocide in 1994, and the Balkans atrocities bookended by the Srebrenica massacre in 1995 and the Kosovo intervention in 1999. One of these crises was African, the other European.

R2P is a global norm that, in the allocation of solemn responsibilities of protection, does not discriminate on grounds of nationality, race or religion, but applies equally to all. As such it speaks eloquently to the highest UN ideals of international solidarity. Just as the UN is the symbol and site of the full family of nations, so R2P is an acceptance of the duty of care by all of us fortunate enough to live in zones of safety towards our fellow human beings trapped in zones of extreme danger.

RAMESH THAKUR Former UN Assistant Secretary-General who served as a Commissioner of the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty and was one of the key authors of the Commission’s 2001 report on the responsibility to protect

Photo: Stained glass window at the UN © Mitchell_Center via creative comms