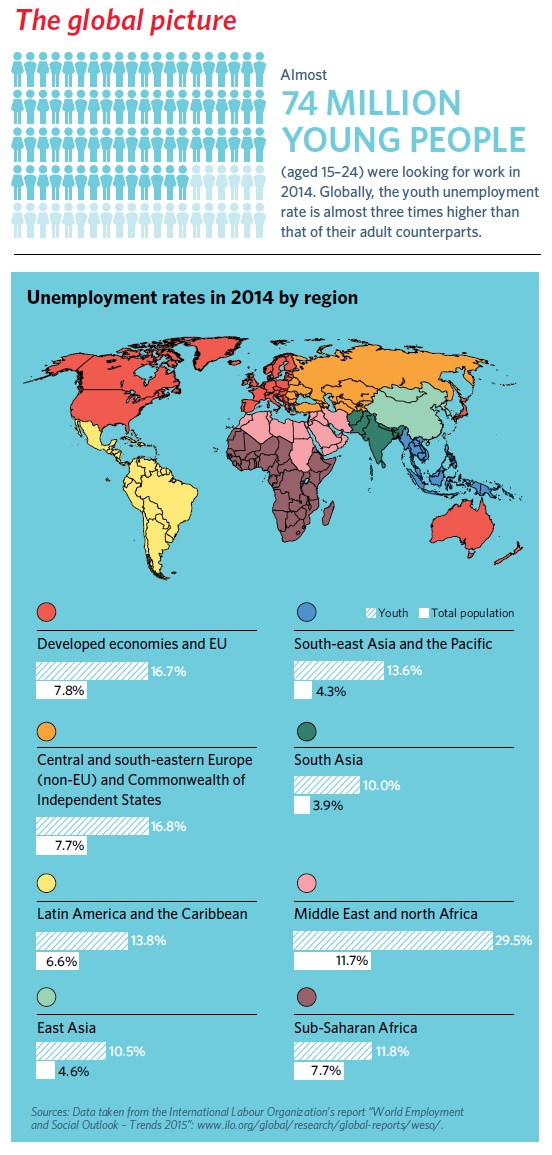

Around the world almost 300 million 15 to 24-year-olds are not in education, employment or training. In developed economies, unemployment is one of the most difficult crises facing policymakers. Greece and Spain, with youth unemployment rates in excess of 50 per cent, are an illustration of how acute and painful this problem can be. The International Labour Organization, a UN body, has spoken about a “scarred” generation of young workers around the world, and has a major programme dedicated to tackling the issue.

This problem isn’t just confined to developed countries. Commentators and experts have spoken of Africa’s demographic boom as a blessing for its long-term prospects. The population of 15 to 24-year-olds in Africa is expected to rise by more than a third, to 275 million, by 2025. In Rwanda, young people between the ages of 18 and 35 make up 40 per cent of the country’s 11.5 million population.

However, harnessing this demographic dividend poses a policy challenge for us, too. As our own economy continues to grow towards middle-income status, expectations among the young for stable, decent, paid jobs has also grown. Every day I meet young graduates who ask me about their career prospects in an increasingly globalised and competitive world.

We have made some progress. According to a recent household survey conducted by the National Institute of Statistics in Rwanda, only 4.1 per cent of Rwanda’s youth are now unemployed, but a bigger proportion remains under-employed in the informal sector. The challenge is therefore far from over – as both population and expectations rise, we have to keep working to enable our ambitious young people to find decent jobs.

So what are the lessons that I have learned as a policymaker?

First, growth matters. Continued strong economic performance is the key to providing foundational conditions to unlock jobs. But while growth is necessary, it is not sufficient. Improving education, especially technical and vocational training, as well as expanding health coverage across the country is crucial in order to give people the skills and well-being to be productive in the workplace.

Second, ICT (information and communications technology) matters. Rwanda’s Vision 2020, the cornerstone of our strategy, aims at transitioning from an agricultural to a knowledge-based economy. In 2014, the ICT sector grew at 25 per cent, ahead of the 7.1 per cent average GDP growth, and contributed more than 3 per cent to GDP – more than all agriculture exports combined.

The only way to ensure that this growth is sustained and its impact is multiplied is to ensure that all citizens are connected, financially included and digitally literate. We will extend high-speed 4G LTE internet to 95 per cent of the population by 2017. Under the leadership of President Paul Kagame, the country’s education is undergoing massive digital transformation. One laptop per child is more than just a policy headline; it is our long-term bet for providing our youthful population with the skills to make them competitive in the global knowledge economy.

Third, empowering girls and women matters. A critical element of any successful employment strategy – and often overlooked – is the role of women. In Rwanda 64 per cent of parliamentarians are women – the highest proportion of any parliament in the world – and gender rights are enshrined in our constitution. There are laws in place to give women the right to inherit land, share the assets of a marriage and obtain credit. Women are leading the way in Rwanda’s next generation of entrepreneurs and we hope they will inspire others to think about starting their own business.

Fourth, private sector leadership matters. The best source of employment generation is not government but the people themselves. So as policymakers, perhaps our greatest challenge is how to create the conditions for small and medium enterprises (SMEs) to not only survive but thrive. 98 per cent of all new jobs are created by the private sector and more than 90 per cent of them by SMEs.

Innovation hubs, like Kigali-based ‘knowledge Lab’ (kLab), help young people turn their ideas into viable businesses. At kLab, young Rwandans are mentored and empowered with entrepreneurial skills which enable them to enhance their future prospects for employment by creating their own jobs.

Fifth, ease of doing business matters. Since 2004, Rwanda has substantially improved access to credit, streamlined procedures for starting a business, reduced the time to register property, simplified cross-border trade and made courts more accessible for resolving commercial disputes. Rwanda is among the few countries where the executive branch has made private sector development a priority by establishing institutions such as the Rwanda Development Board, whose main purpose is to design and implement business regulation reforms. These measures are clearly beginning to have an effect, with the World Bank ranking Rwanda as Africa’s third most business-friendly destination.

The generation of young people who have grown up over the last 20 years since the genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda have proven themselves to be brave and resilient. Now we must create the conditions for this generation not just to do well, but to excel.

Jean Philbert Nsengimana is Minister of Youth and ICT for Rwanda