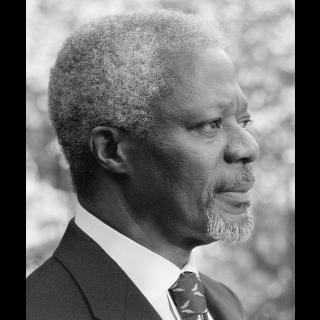

We give the last word to Kofi Annan, the former UN Secretary-General who died on 18 August 2018 having dedicated over half a century to peace, development and human rights for all. This is an edited version of his opening remarks at the 2001 World Conference on Racism in Durban, South Africa.

Let us remember that no one is born a racist. Children learn racism as they grow up, from the society around them – and too often the stereotypes are reinforced, deliberately or inadvertently, by the mass media. We must not sacrifice freedom of the press, but we must actively refute pseudo-scientific arguments, and oppose negative images with positive ones – teaching our children and our fellow citizens not to fear diversity, but to cherish it.

Often discrimination veils itself behind spurious pretexts. People are denied jobs ostensibly because they lack educational qualifications; or they are refused housing because there is a high crime rate in their community. Yet these very facts, even when true, are often the result of discrimination. Injustice traps people in poverty; poverty becomes the pretext for injustice.

In many places people are maltreated on the grounds that they are not citizens but unwanted immigrants. Yet often they have come to a new country to do work that is badly needed, or are present not by choice but as refugees from persecution. Such people have a special need for protection, and are entitled to it.

In other cases indigenous peoples and national minorities are oppressed because their culture and self-expression are seen as threats to national unity – and when they protest, this is taken as proof of their guilt.

In extreme cases – alas all too common – people are forced from their homes, or even massacred, because it is claimed that their very presence threatens another people’s security.

Sometimes these problems are in part the legacy of terrible wrongs in the past – such as the exploitation and extermination of indigenous peoples by colonial powers, or the treatment of millions of human beings as merchandise, to be transported and disposed of by other human beings for commercial gain.

The further those events recede into the past, the harder it becomes to trace lines of accountability. Yet the effects remain. he pain and anger are still felt. The dead, through their descendants, cry out for justice. The sense of continuity with the past is an integral part of each man’s or each woman’s identity.

Some historical wrongs are traceable to individuals who are still alive, or corporations that are still in business. They must expect to be held to account. The society they have wronged may forgive them, as part of the process of reconciliation, but they cannot demand forgiveness as of right.

Each of us has an obligation to consider where he or she belongs in this complex historical chain. It is always easier to think of the wrongs one’s own society has suffered. It is less comfortable to think in what ways our own good fortune might relate to the sufferings of others, in the past or present.

A special responsibility falls on political leaders. They are accountable to their fellow citizens, but also – in a sense – accountable for them, and for the actions of their predecessors. We have seen, in recent decades, some striking examples of national leaders assuming this responsibility, acknowledging past wrongs and asking pardon from the victims and their heirs. Such gestures cannot right the wrongs of the past. They can sometimes help to free the present – and the future – from the shackles of the past.

But past wrongs must not distract us from present evils. Our aim must be to banish from this new century the hatred and prejudice that have disfigured previous centuries. The struggle to do that is at the very heart of our work at the United Nations.

This conference has been exceptionally difficult to prepare, because the issues are not ones where consensus is easily found. Yes, we can all agree to condemn racism. But that very fact makes the accusation of racism, against any particular individual or group, particularly hurtful. It is hurtful to one’s pride, because few of us see ourselves as racists. And it arouses fear, because once a group is accused of racism it becomes a potential target for retaliation, perhaps for persecution in its turn.

Nowhere is that truer today than in the Middle East. The Jewish people have been victims of anti-Semitism in many parts of the world, and in Europe they were the target of the Holocaust – the ultimate abomination. This fact must never be forgotten or diminished. It is understandable, therefore, that many Jews deeply resent any accusation of racism directed against the State of Israel – and all the more so when it coincides with indiscriminate and totally unacceptable attacks on innocent civilians.

Yet we cannot expect Palestinians to accept this as a reason why the wrongs done to them – displacement, occupation, blockade, and now extra-judicial killings – should be ignored, whatever label one uses to describe them.

Let us admit that all countries have issues of racism and discrimination to address. Let us rise above our disagreements. Let us echo the slogan that resounded throughout this country during the elections of 1994, at the end of the long struggle against apartheid: sekunjalo. The time has come.

UNA-UK joined people the world over in paying tribute to Kofi Annan, who served as UN Secretary-General from 1997 to 2006. You can read an obituary prepared by his speechwriter Edward Mortimer, reflections from other friends and colleagues, and a selection of his articles and speeches at www.una.org.uk/kofi-annan.

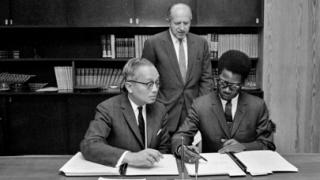

Photo: Kofi Annan in Oxford in 1999. Credit UN Photo/Evan Schneider