A short history of the impact of discussions surrounding self-determiniation on north-south and south-south relations.

It is not unusual to hear long sermons and heated debates at the UN with states defending cultural relativism and state sovereignty against the universality of human rights and vice versa. They play on stereotypical ideas of a West that defends human rights and a global South that is defending its sovereignty and cultural heritage.

Behind these theatricals lie complex dynamics. In reality the picture has never been black and white.

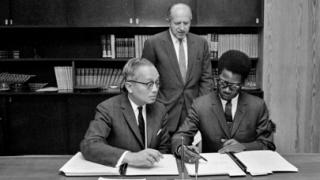

The story of the right to self-determination, for example, reveals a kaleidoscope of intergovernmental human rights discourses, geopolitical manoeuvring, colonial and post-colonial struggles – as well as tacit agreements between political elites in developing and developed states. Some decades ago in the 1960s, you had the reverse of the dynamic we see now: states from the global South leading the creation of the modern international human rights architecture through the adoption of several key human rights conventions – including the Convention on Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination and the two Covenants that form the International Bill of Rights. These treaties allowed for human rights to be approached from beyond sovereign national boundaries. Much of this work took place in the context of the decolonisation and anti-racism movements. Both these movements have a common connection to a key aspect of human rights – the right to self-determination.

Early in the 20th Century, the idea of self-determination found expression within an intergovernmental setting at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. Prior to the Conference two new emerging powers – the USA and USSR - had already begun to articulate the idea of self-determination, as reflected in statements by both their leaders: Lenin’s Peace Decree and Wilson’s Fourteen Point Plan. The Conference settled the breakup of the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Turk empires. It positively considered self-determination for European territories (there were minor exceptions: Danzig, Memmel territories and Saar). Territories outside Europe such as Cameroon, Palestine and Syria were treated very differently. Through the League of Nations, a mandate system was created with a three tier grading system based on the ability of people in these territories to govern themselves. In effect non-European peoples were deemed unfit to govern themselves independently.

Towards the end of the Second World War self-determination gained popularity and was made into an international principle in the fight against fascism. In the aftermath of the war, as the world polarised between the United States and the Soviet Union the principle got a careful mention in the UN Charter but was not included in the Universal Declaration on Human Rights (UDHR). The transformation of self-determination from a principle to a right took place only in the 1960s at the insistence of newly independent states from Asia and Africa who demanded its insertion in the International Bill of Rights – albeit with a vague definition.

In practice and interpretation, self-determination has been heavily restricted to decolonisation under the principle of uti possidetis. This in effect guarantees that colonial borders will not be altered despite new states coming into being. The anti-colonial movement’s efforts to make self-determination a right thus indirectly ensured the sanctity of colonial borders. There is in fact little to show that postcolonial governments strongly opposed the uti possidetis principle and in postcolonial states political elites readily accepted the principle. Subsequently these states acted as one of the staunchest guardians of this principle so as to ward off any claims of a right to self-determination by communities within their borders – in many cases at the cost of instability, conflict and thousands of lives.

Bangladesh’s independence in 1971 may seem like an exception. However it must be noted that here to the boundaries of the British colonial partition of Bengal and the subsequent colonial partition of India were followed.

Having thus partly closed the chapter on one aspect of the right to self-determination they began to focus on another: In the 1960s several postcolonial states began emphasising the importance of the right to economic self-determination and permanent sovereignty over natural resources. These arguments culminated in proposals for a New International Economic Order in the 1970s and eventually played a key role in shaping ideas of international development.

In the 1980s and 1990s, nearly seven decades after the Paris Peace Conference, history came around full circle when the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia were dismantled and regional arrangements were made to recognise self-determination as a justification for altering borders within these regions. It could be argued that most ex-Soviet states followed former boundaries of constituent states within the USSR. This however is not the case for Yugoslavia: a federation which was dismembered on the internationally approved basis of self-determination. The only exception was the subsequent unilateral declaration of independence by Kosovo, which remains disputed.

In the meanwhile, outside Europe, ideas of economic self-determination quickly fell apart with the end of the Cold War and the changing world order. By the 1990s and 2000s all that remained was a convenient rhetoric for political elites in the global South as they negotiated their economic well-being in return for access to markets and resources for companies and institutions from developed states.

International discourse is in flux as ever and is currently very turbulent indeed. Increasing extreme right wing populism across the globe has spurred a new wave of virulent nationalism. States like the US have openly threatened multilateral intergovernmental processes that underpin the current global political architectures. National borders have been increasingly questioned within former colonial powers such as Spain and the UK. Globally, a new cold war is well in place with increasing competition between states like China and Russia and a divided West. In such times the right to self-determination is sure to come back into the limelight. However, there is no indication that decades after decolonisation, the international community is finally ready to look beyond colonial socio-political and economic boundaries – within which the right to self-determination is condemned in perpetuity.

Photo: South Sudanese queue to vote in the 2011 referendum on self-determination. The results would lead to the creation of the world's youngest country. UN Photo/Tim McKulka